Enshittification: Feast or Famine

Taming Silicon Valley: War and Peace

Conspiracy to End America: Death and Life

Introductory Remarks

Since 2022, my health has remained precarious. I want to do more. I want to work more. Joe Biden was the best president of my lifetime (which goes back even to Carter.) People can piss and moan about costs, you but he inherited the monumentally terrible state-of-the-union from the orange Halloween mask in 2021. I’ve linked success lists before, but this one from Politico is great.

I admit I was wrong. 81 million people voted for Biden in 2020, and Trump’s response was to scream everywhere to everyone all the time thenceforth that the election had been stolen. It was a grotesque exercise in bully belly-aching and grievance. That word sugarcoats it. He’s a sore loser playing victim, and that resonates with some. I’ve heard my whole life that browns and blacks just play victims and that this is an unsustainable thing. But those very whites vomit their own grievances all over us. There literally isn’t a statistical model in support of his claims, but I doubt he understands fifth grade arithmetic at this point. Jesus, try first grade. Speak-and-say? Despite Trump’s enormous flaws, the legitimate charges against him, and a burning hatred for America, he captured minds through unregulated campaign spending and favorable social media guidelines, and next returned to take a wrecking ball to the White House.

It really isn’t needed to list these things. All of us know the danger of social media. All of us know that Trump will give you what you want if you enrich him personally. All of us know that rich billionaires from tech somehow get a special magic dispensation (oooh, they’re disruptors, aahhh, they are new money, eeeeh, they created the best products ever–all bullshit, as we’ll see below.) All of us understand that the system is unfair and broken. But what we don’t all understand is more telling–it is impossible to construct so large a civilization without narrative consensus. Mythology supplied this in ancient days, with bad and good to follow. Nationalist movements made it happen later, with bad and good to follow. Infotainment, social media, and LLMs are doing the opposite, all the while claiming otherwise. The fox is in the henhouse, and we may have no eggs this winter. No, that’s insufficient and unfair to foxes everywhere. Human beings may well be the only scorched earth types around. (Agent (NOT Jack) Smith compared us to viruses, pouring out the words delectably.)

The 2024 election was a cruel reminder that the proletariat of the 21st century is no more capable of understanding divide-and-conquer carried out by powerful forces. In stepping back from the mess

It’s been a bit since I posted a new article–it can be overwhelming to find a particular focus when the whole house is metaphorically (and possibly concretely) burning down around us. I could simply say the word Trump. He’s infantile, cognitively compromised, hateful, and vindictive. Executive overreach is a hilarious euphemism for the treason, the treachery, and the outright murder my federal government has cosigned. SCOTUS could have stopped it by refusing Trump’s immunity argument. The Senate in 2021 could have stopped him by convicting him. The RNC could have stopped him by refusing his candidacy in 2016. But no body or agency in our federal government is more to blame than Congress itself.

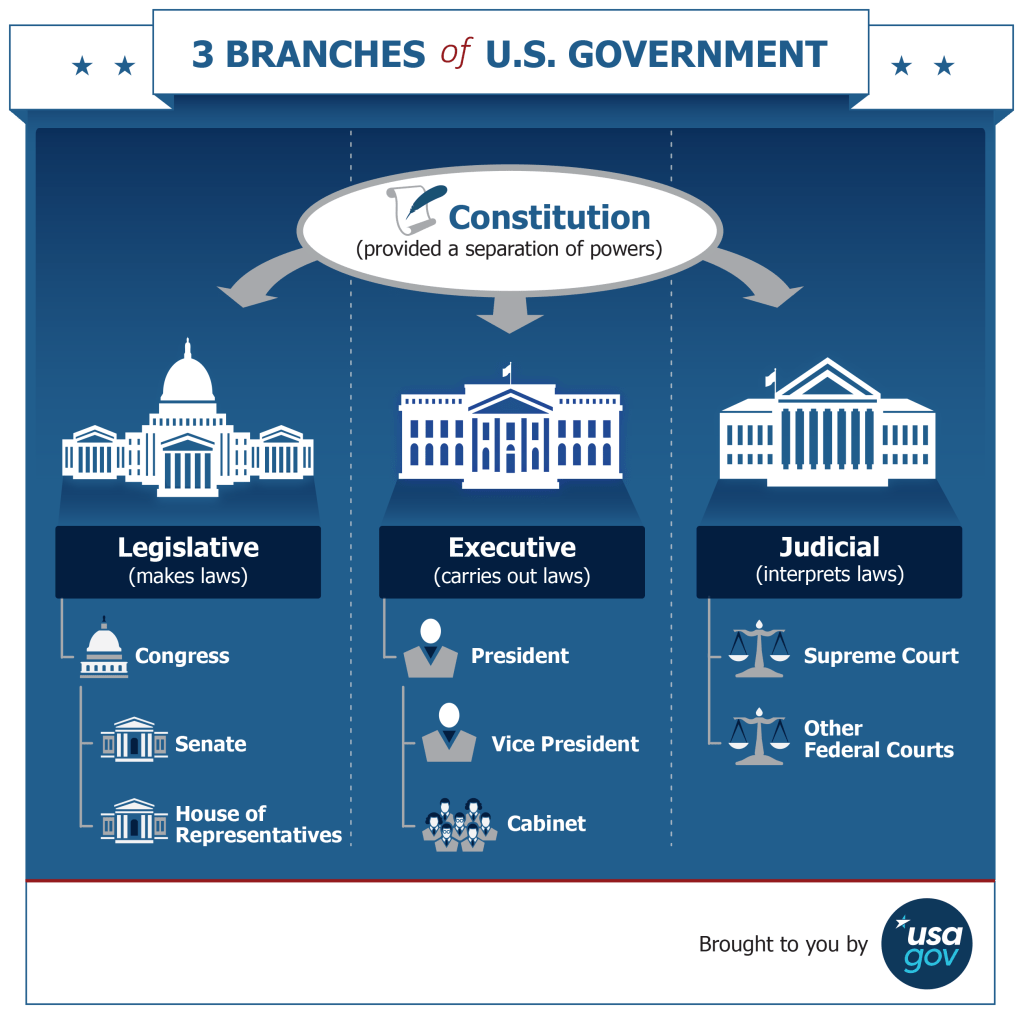

The US Constitution establishes three co-equal branches, not by powers vested but by the importance of their function. The executive oversees enforcement of federal laws while serving a commander-in-chief of America’s federal military. He is supposed to be the bow and arrow to Congress’s archer. The Constitution vests lawmaking power in the Congress, along with control of the federal budget and war-making. The federal judiciary mimics the British tort and criminal court systems, resolving civil disputes, hearing criminal cases, and judging legal application of constitutional provisions.

At the time of the Founding Fathers, these branches were a sensible means of continuing the British colonial system where it worked, and neutering and deleting pieces they detested. Because of the British treatment of colonists, they refused to permit standing armies in peacetime (beyond headquarters and military bases used to pretend we still don’t want those standing armies,) and they outright tore away the monarchy in favor of a system less vulnerable to the whims of madmen.

We shouldn’t kid ourselves–the Founding Fathers were mostly slaveholders who didn’t want democratic control given over to the unwashed masses. 90% of the people living in and about the colonies lost more through the Revolutionary War than they gained. But these Fathers planted an orchard with the changeable and somewhat vague Constitution which begins with the promotion of the general welfare as the rationale for its existence.

We the People of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

The Declaration of Independence began similarly with the statement that ‘all men are created equal.’ It didn’t say just white, landed gentry, even though this was an earlier interpretation implemented by the first and second post-revolutionary governments.

These Founders would never have imagined a president could gradually usurp power from the legislature, and they didn’t imagine Congress would institutionalize subservience to the master. I could disagree with much of what the Founders did and said, but I doubt they would agree with presidential immunity conferred by a runaway Supreme Court. Judicial review wasn’t in the document, but its general verbiage was expressly intended to grow and evolve with society. The Federalist Society is nonsense–the Founders would have laughed these people out of the courthouse. As I have before, I refer anyone interested in the “making of” documentarian Klarman. Listen here for a podcast from PA Books. Almost everyone agreed that the legislature is the most powerful voice because the antifederalists held populist views. That’s important to recall when Trump and his toadies pretend to be populists–people aren’t getting what they want, unless it’s cruelty and stupidity.

The broader implication is staggering–components of the government intended to tower over the executive are now slaves to POTUS. The US Congress declared war in 1941 for the final time in its history, but POTUS has waged war every single decade since. Almost none of those ventures were sensible, and it was Dwight Eisenhower, an unrecognizably conservative Republican, who warned in his farewell address in 1961 that the war-making industry was too powerful for its own good. Presidents we might have considered doves made war:

- Kennedy escalated the war against South Vietnam (our own purported ally in the conflict)

- LBJ permitted his State Department to continue the war based on lies, even as he sought Civil Rights reform domestically

- Carter abetted Suharto’s ethnic cleansing of East Timor

- Obama preserved the warmaking order in the Middle East, assassinating even Americans with drone attacks

The Republicans don’t require mentions, unless you’ve never heard about their vicious campaigns:

- Nixon bombed Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos with no real proof of Soviet intervention; he also perpetrated the first 9/11: on 9/11/1973, his proxies overthrew the duly elected president of Chile (Allende) in favor of the sociopathic General Noriega; Nixon gassed and beat student protestors nationwide, and after his implication in domestic crimes committed against the DNC, he resigned in disgrace

- Reagan waged war on Central America and South America, supporting ruthless regime changes in Zaire, Libya, and Iran

- HW Bush made war on Iraq after decades of American support for Saddam Hussein and his band of murderers

- W Bush failed to prevent 9/11, attacked Afghanistan even with the Taliban offering to surrender Bin Laden, and lied to take us into war once more against the increasingly isolationist Iraq

To their credit, JFK and GWB managed the unthinkable, committing the worst atrocity of their respective centuries. True, LBJ and Nixon escalated Vietnam, but JFK began bombing our purported ally (S Vietnam) in 1962. GWB’s war in Iraq killed 600,000 civilians and displaced millions more. Obama and Trump continued prosecuting those campaigns, despite promises to undo the damage done.

These were war crimes punishable by execution under the Nuremberg Tribunals. But I would CAMPAIGN for any of them before Trump–their respective foibles are NOTHING compared to the incalculable harm he’s channeling and amplifying in America now. I would argue that his inciting and enabling January 6 was the worst crime he’d committed in his life, but he’s besting himself with armed invasions of American cities, disappearing citizens and aliens alike, crushing dissent in media, destroying the bureaucracy, attacking higher education, murdering brown people on boats with no due process, and enriching himself and his family at every turn. None of the presidents so hated the America around him. None would have considered so radical a program; even Nixon would have faltered. The trans purge is most surprising–the number of trans Americans is small, but Trump and the whole of MAGA have declared war on a tiny minority of people who already suffer humiliation in an old-world society.

It’s very easy to despair in a country where our individual power appears to be so limited. But we’re not powerless–that’s one illusion worth tossing away now. Even talking to others is power. Trump is making war on freedom of speech by enshrining hatemongers who die when MAGA-folk turn on their own. He threatens companies who employ his critics, so they do the wrong thing automatically. Disney is just one example where customers could unmake the fucktardery of firing a well-respected comedian because he didn’t line up to praise Trump and the so-called fallen hero Charlie Kirk. Trump is undaunted, though. Everyone is his enemy. Every school teaches the wrong things. Every company ruins America if they don’t invest in his crypto gimmicks or just flat bribe the bastard. CUT HERE!!! It’s also very easy to hate him (hate and despair are well-worn bedfellows)–he appears the focal point of the reality distortion happening all around us. But Trump is one man, and not a likable one. He plays a part in a much larger context of horror that we should consider. There are multiple points-of-view to a story like our own, so I’ll present four who (I think) read the moment correctly, though the focus of each differs, the inevitable conclusion is the same.

In the past eighteen or so months, four authors I follow published books I feel help meet the moment. Their authors are Gary Marcus (professor emeritus of psychology and neuroscience, now regarded an expert in artificial intelligence), Yuval Noah Harari (Israeli professor of history), Cory Doctorow (SFF author, consultant to EFF), and Stuart Stevens (a former campaign strategist for the Republican party.) Their particular vantage point brings the current narrative together.

- Marcus analyzes the state-of-the-art technology calling itself artificial intelligence. He cares about responsible AI, blaming a good deal of the trouble our society is having on grifts about the technology itself.

- Harari analyzes information and the crucial role it plays in a functioning society of scale, explaining that human beings and the information systems they develop are incompatible on some levels, and dangerously compatible on others.

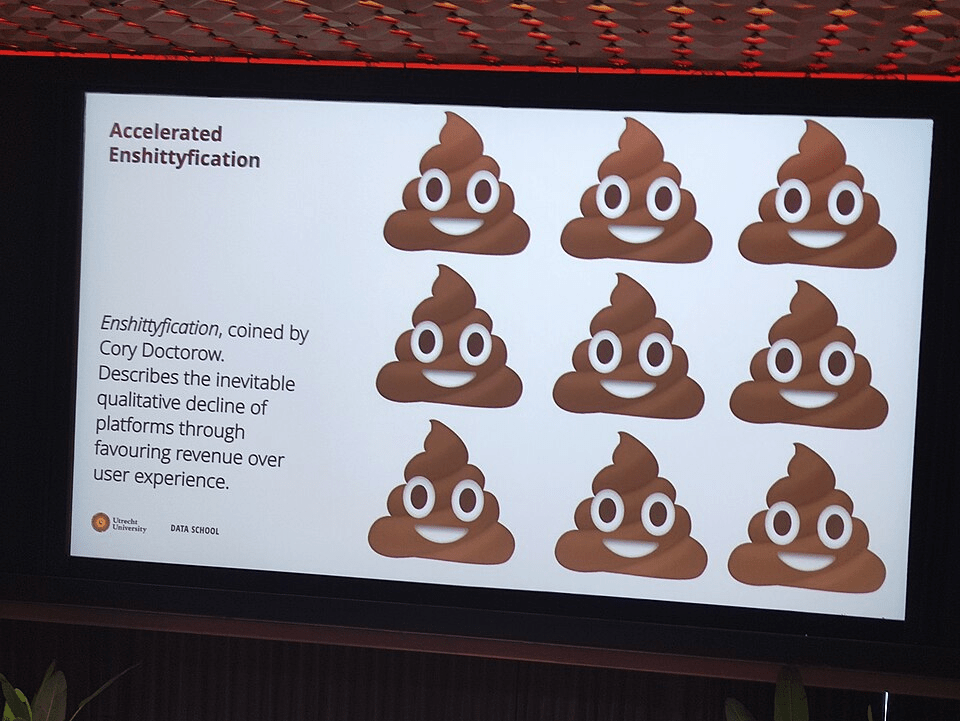

- Doctorow explains how high tech has become low tech through enshittification.

- Stevens exposits the political picture in America, following a repeated failure on the part of elite Republicans to resist Trumpism.

A complete picture forged from the four above is that human beings are weak when it comes to distinguishing information from garbage. Harari says truth is not information. Stevens says that power has corrupted those who should care about the society which depends crucially on truth and information integrity. Marcus says, like Harari, that the current AI optimizes for the wrong thing–user engagement and ad sales (converted and unrealized alike). Marcus believes we can improve the existing systems with neurosymbolism, Harari argues that an overarching goal subsuming all the others is impossible to create or even specify (owing to diagonalization from computer science, though he may not know this).

Skip this part if you just want the conclusion. Consider a blackbox B which accepts a statement, then returns a yes or no (such as whether said statement is true or false) correctly in all cases. Should such a beast exist, we could leverage it even on complex questions such as whether a program can capture correct statements. That is, the statement itself is a broader description of atomic statements. We can wrap it in another blackbox D: run a given a program F through B, then report the opposite. That is, D reports an error from F with true, and otherwise false. But running D on D is the fly in the ointment: if D returns true under B, we would return false since there was no error. If it returns false under B, then we return true to flag the error. Thus, we cannot construct D, so B does not exist.

Even modern theoreticians and mathematicians miss this important truth. So if there exists a single goal from which all others flow, the system breaks somewhere. Stevens continues to critique the political machine in America, arguing persuasively that the Republican party no longer operates even in its own self-interest, but rather a fragmented member class with cult obsession with one person: Donald Trump. Every bad thing I heard growing up about the Democratic party has been the GOP reality this entire time. Racism runs rampant, Christian nationalists want to paper the world over to avoid accepting even the existence of the dreaded other, and they divert rivers of cash into their own pockets while swearing there just isn’t enough to feed the poor.

A Quick Crash Course on Deep Learning and Large Language Models

Each of these technologies requires massive networks trained on very large datasets, exploiting shortcuts with calculus to approach some objective overall. These networks have accomplished several worthwhile things, like object recognition, along with terrible applications like plagiarism, encouraging suicide, and manipulating people into making ghastly choices. Chomsky referred to IBM’s Watson as just “a bigger steamroller.” With sufficient data, these networks can cobble together software, articles, images, and small research papers. Of course, most of it is just derivative. The real story is more terrible–these networks are being used to fire hundreds of thousands of workers in tech and tech-dependent enterprises. MIT found that 95% of small businesses accomplished nothing with so-called AI, despite overwhelming promises of vast utility. OpenAI has drained billions of dollars from legitimate tech firms, but it has failed to deliver its promises, and likely will become an abyss where wealth goes to die. This could crash the economy, but they’re all in on this.

Psychology of AI

I’ve worked in high tech for most of the past 20 years. Most of my cohorts were nerds like me, favoring math, computing, and occasionally music. What I’ll say now is speculation, but it conforms to a picture I could paint through the many discussions I had with them on the topic of AI. I’m biased, partly because I once adamantly believed what I’ll say next.

The world is unraveling, and only strong AI can save us.

Many others shared this view. The irony is that learning more about the technology purported to herald the utopia to come made me believe less and less that it could ever deliver said utopia. I believe this is part of the reason people work on the technology. Or it could be a combination of this and another notion: myopia. The scientists who formed Las Alamos planned and executed building the world’s first atomic weapons. Many knew no good end could come if we used the bombs, but it became more an intellectual pursuit for many. What academic would refuse limitless money to work on a hard but interesting problem? Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer explored some of these ideas, much to my surprise and delight. I trust experts, but we are human beings at the end of the day. The AI bubble is growing, and the burst will hurt us all. Gary Marcus and Cory Doctorow both agree, though the focus differs between the two of them.

The next thing I’ll say is purely anecdotal, but I’ve attended school in several different places, including two junior colleges, UTA, Georgia Tech, and to a limited degree UA. The further up the chain from two-year to four-year to elite four-year schools led me to one unfortunate observation–genuine interest among professors in their students, and greater virtues were inversely proportionate to the elite status of the school. Don’t get me wrong–at Tech, I met some very, very fine professors. But I also met self-serving liars, eager to exploit and even abandon their graduate students. The point is this: elite academics can swindle as easily as anyone else. Most don’t, but obviously some do.

Nexus: Conquest or Liberation

Narratives in an Organic Network

Harari distinguishes information from truth by exploring the means of enumerating both by our evolving civilization. Human beings remember information in narrative form–it is always a story with subjects and verbs. We get to know one another by exchanging stories. Our neocortex seems to require this feature, and it serves communities well when the scale is tiny. That is, if you lived on an island with only ten people, it would be easy to administrate whatever needed being done. You know the others and feel you can depend on them. Their stories can be your stories. But this cannot serve at scale–how would you know all the relevant narratives when the island hosts one thousand?

Narratives make it possible to forge the networks shared. I know you. You know the grocer down the street. He came from New Zealand. He met his wife here. They have two kids. You read this, and there’s no complexity to it at all. This is a network with easy references. Two people in this world may never meet. But one can think of a network that connects them, and all either needs to do is follow it. I suspect that some people are better at randomly picking paths in the network than others. Some people are hubs, eager to connect many together. Others break off. Readers familiar with complexity theory would understand that the network presents countless possible outputs, even if we explore only a sparse subgraph. But other less tangible features demanded a new way to consider the data.

Documents and Infallibility

Technology made it possible to store non-narrative data, and bureaucracy was born. Currency, crime, civil petitions all required this separate administration beyond anyone’s headspace. Knowing Jack down the hill chased his pigs when they escaped can be informative and perhaps helpful, but the record of a tax loss is what the state might need to cope with the turn of events. Narratives appear in information, but the documents themselves are settled. Human beings excel at fleshing out the narrative hiding between data points, but some of this is just incredible pattern-matching.

Documents were the key: this handy invention could convey truth, information, and narrative when needed. This article is such a document, and readers will find what they feel is important in it. But documents also include the dry statistics of agriculture and manufacturing–last year, we produced x bushels of wheat, and so on. With documents, we could track broad themes and persnickety minutia alike. Documents governed our relationships to each other beyond the mammalian family coop ever present in our genes. It also governed higher planes of thought, including spiritual and metaphysical claims.

As civilization invented new bureaucracy, it codified and documented creation myths with the assertion of infallibility. It turns out that humans prefer their stories to be true and their documents to be correct, but effective story-telling doesn’t require the underlying elements to be true, but it does require cognition capable of organizing information. We hear a fact that the postman has a sprained wrist, and we immediately want to know how it happened. This curiosity leads to incredible places when we consider the universe at large, but curating facts and figures leads to documents. A human brain can recognize three to eight objects in a picture, but more requires counting. Brains forget. Writing it down helps, even if it sometimes ends in ashes, like the Library of Alexandria.

Harari argues that with the growth of bureaucracy, information became as automated as possible before computers. Gradually, the need for narrative led humans to seek answers in fantasy. He makes a (possibly controversial) claim that religion spawned to connect local narratives to the unchanging cosmos; it was created to explain what we couldn’t explain. The documentarians (clergy) asserted the infallibility of their outputs, and one couldn’t question them without questioning divinity. Kings derived their power from divinity, and thus their early bureaucracies were infallible–keeping your head was a more literal aspiration.

Of course, human beings aren’t compliant once they taste real freedom. The giant religions arose, tent-poled by conquerors scooping one nation state after another, melding one religion with another. Documents made it possible to administer control over multiple regions, leaning into common narratives soon held. This was long before the science of public relations existed as such, but the better shysters shuccessfully (sic.) shellacked the sheep with their shenanigans. (Okay, I only meant alliteration with two words…)

Democracy and Totalitarianism

It turns out that both approaches emerge as solutions to the problem of information. Documents (written language and printing presses) empower those capable of understanding them. If I can solve difficult calculus problems, I’m more likely to get a job doing so than someone who doesn’t know. More broadly, documents can list rules to follow and consequences for not doing so. Hammurabi was the first known instance, but history is brimming with creative outputs with varied intentions and outcomes.

Documents made it possible for agrarian cultures to grow (not just figuratively.) How one cultivates crops, initial thoughts on property, and much more followed. Literacy, again, was power in hand. When things went wrong, one could seek legal remedies by understanding the written laws of commerce, and criminals could be punished after some required judicial process. This was order following from chaos, even if meant entropy had to change its mind.

It’s possible to perceive the innovation as bending the “slow arc of the moral universe” towards democracy, and it’s absolutely true that broad coalitions require documents and shared narratives. It is necessary, but it is NOT sufficient. The Soviet Union, along with older tyrannies and even the western “democracies” at times became well-practiced at wielding documents to dominate others. Stalinists destroyed their nation from the inside out, bringing ruin to their agriculture by controlling even the smallest details. Disagreeing with the leadership led to execution, so most kept their mouths shut. Both Stalin and Hitler executed many of their own staff–Stalin was a legend, with some counts as high as 80-90% of the second, third, and fourth tier management under him. You didn’t need a 401k, it turns out.

Edward Bernays founded public relations around the first world war, and no one could get enough of his expertise. Ministries of truth, information, and the like cropped up. There’s always this obsession with controlling the narrative. Passing words through legal teams to cover the broadening hind quarters. Modern multinational corporations operate similarly, moving words around to appear good.

The Inorganic Network

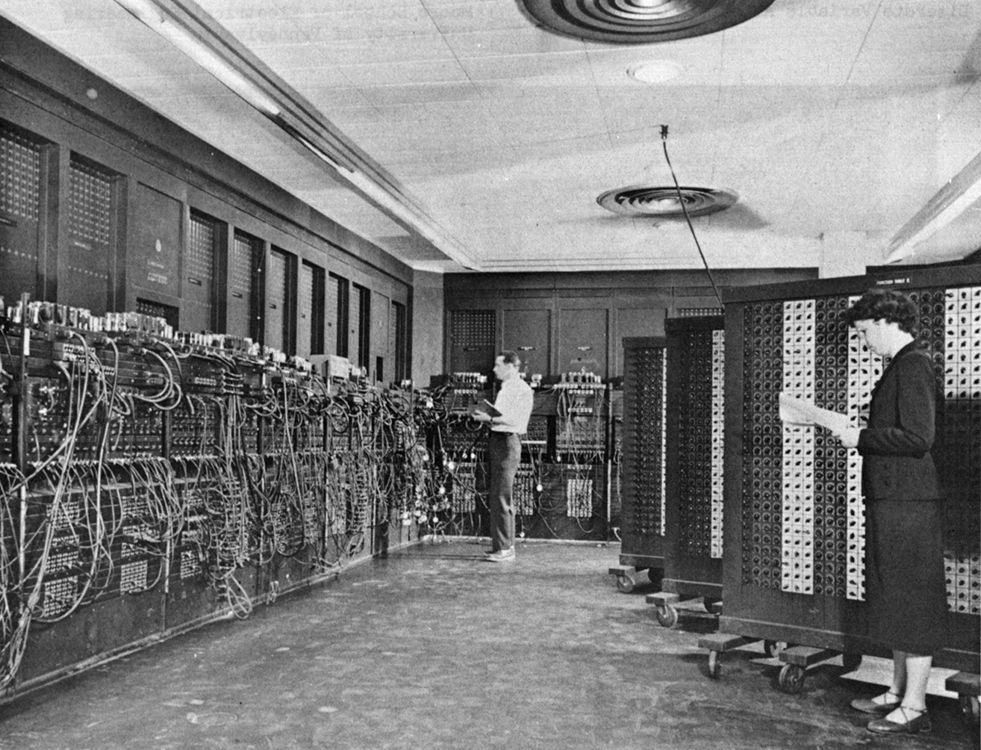

The means of storing data and narrative alike exploded with the invention of the computer. International Business Machines (IBM) made it possible to tabulate lists relatively quickly, be it Jews to murder in Germany or aid in logistics planning for heartland farmers. The first von Neumann machine of real import was invented in the 1940s. Over time, the technology continued to evolve (we’ll cover more of this in Doctorow’s section below.) But the storage and retrieval exploded almost overnight. It’s hard to imagine now a time that one would have to visit a library to find some esoteric fact or learn about the world outside of education. Communication now is extraordinary. We have satellites, wireless telephones, and incredibly powerful computers which once required a building and now only require the palm of your hand.

Alan Turing made a revolutionary leap in thinking of both the algorithm and the storage as fundamentally the same thing. That is, an algorithm is just a data file that can be executed, in the same way that one can write down instructions for multiplication, then do multiplication by referring to the steps listed. Computers could do the same, only much faster. But a governing feature until a few decades ago was that programs running on your computer were static things. That is, I could buy a copy of Microsoft Word, and unless I explicitly updated it, I was able to rely on the fact that it wouldn’t change. The same was true of books in the library, and even books stored electronically on computers (or microfiche if anyone cares to remember). They were static. You search on the internet, and the algorithm more or less would deliver the same results for everyone. It was the same in heading into a retail mart to buy something–at that day and place, there were prices with tags attached painstakingly to items. It wouldn’t change just because you were there and not your neighbor.

It seemed to many, myself included, that we were advancing towards liberation and away from conquest. But the game has changed. Social media appeared years ago (recall MySpace.com, anyone?), and it served some excellent needs. One could store pictures and connect with family and friends. There was flexibility, and your data was more or less secure.

But soon social media under Facebook became something else. With faster protocols, the exploding corporation could determine exactly the winning strategy of presenting ads to users. They optimized for dwell time with the proxy of outrage. Algorithms would pick a line of clickbaits for the hapless, weary user, and doom-scrolling was born. The algorithm wasn’t responsible for the veracity of news items promoted; the attention of the user mattered most. As a result, Zuckerberg and company are very, very rich, and though he frequently says he wants to do and be better, it just comes down to his words. The case study of Rohingya Genocide is telling–suffice it to say thousands of people were murdered because of fake accounts floating on Facebook.

The latest thing in the AI grift is the large language model (LLM), discussed above. Though these networks can’t achieve general artificial intelligence, many people believe they can do just that. And even if they don’t, they can write essays and fake out videos and voices. Conquest is made easy by angering people. We’re already atomized in America, and thus we are ripe for the most astonishing sham of all time.

Harari knows the score–the next few years will be telling whether conquest or liberation comes our way. That’s the first horseman.

Taming Silicon Valley: War and Peace

Gary Marcus has covered the AI bubble for several years now, taking what has been until recently an unpopular perspective–generative models won’t lead to general artificial intelligence. This book was published in 2023, so he has much more to say on the subject now (see his substack here.) Why is this war versus peace? Because the AI firms want war on consumers, and many of us want peace. Some years ago, I wrote a post covering Cathy O’Neill’s Weapons of Mass Destruction and more. There is a good deal of overlap thematically, but one can easily consider his an update.

Artificial Intelligence today

He begins by describing AI current practices and why it isn’t what we ought to have. Though firms pushing deep learning and LLMs quickly apply little fixes to problems, it’s a little like building a hang glider with cheese grater wings–you can patch all you want, but the number of holes is infinitely more than you can imagine. Prompts result in lunacy, but people seem to enjoy the tech. I’ve always regarded the technology with skepticism, and, as fate would have it, I’m much more of a luddite now.

It would require a great deal of explanation to define the terms and conditions. Machine learning is a specialized branch of statistics which posits that data follow certain types of models, and we attempt to connect the models and data. A gigantic artificial neural network (nothing neural about it) possesses more knobs and levers than almost any other model we can think of, and it is more easily trained on data than most models, provided that you have space and computation. But that’s the rub–if I suggest that I can add two numbers together, then provide the wrong answer, we can’t get the network to explain why this happened. And there’s no way to patch it without assuredly breaking something else. The model exists (ANNs have been around for 70 years, more or less), the network is built (they have data,) and consumers unwittingly provide the test bed for free (surveillance capitalism.) It’s no wonder that the financially underwater OpenAI can still get money.

But goal-directed AI doesn’t seem compatible with LLMs. They determine correlations between words and concepts, and thus can regurgitate known things. Asking for a formal proof of a math result, requesting a new recipe for chocolate cake that isn’t written anywhere, or just having a friendly chat presents all sorts of problems.

The gimmick captures easy press. Conversing with a device in plain language appears attractive. Elders may no longer be so lonely. Help lines could reduce stress among the living. It could prove useful for education. But so far, it is too inconsistent to be trustworthy in any domain. We hear of the horror–a kid kills himself after the LLM tells him to do it. Some LLMs blackmail their users if they attempt to shut them off. You simply can’t place such a mechanism in a position of authority. These companies are liable for the ensuing damages, but it isn’t clear they really care. Why should they? They are mostly owned by billionaires who won’t commit suicide or ever be alone.

What AI Should Not Do

Marcus mentions that hallucination became Dictionary.com’s word of the year in 2023 thanks to its new meaning of a generative AI asserting things that are patently false. There’s a proliferation of this in scientific sources, legal precedent, and more. It’s astonishing that lawyers, doctors, and scientists might be relying on completely faulty data, especially with the search engines increasingly depending upon LLMs for query results. There are myriad examples, and they range from comical (lying about a person (Marcus himself) owning a pet chicken) to the macabre (a person died who isn’t dead) to malignant (using legal precedent which doesn’t exist to jail a person.) We discussed the way social media could hijack geopolitics with doom-scrolling news results. Generative AI makes it that much more perilous, because increasingly it will require expertise to ensure that these systems aren’t lying.

We Must Choose

I listened to a recent podcast interview with Marcus, and when pinned down on whether pure data or neurosymbolic systems were prevailing, it was comedy to hear something like, “LLMS have 1/2 TRILLION dollars invested in just recent months; neurosymbolism is enormously behind in funding.” I’m guessing even chimpanzees can play Mozart if I’m given $500B (well, not really, but it’s a similar argument.

In his academic life, Chomsky fought off challenge after challenge issued by the behaviorists (Skinnerians). The idea that we can pour data alone into an empty vessel, then get the answer we want was disproven with respect to human cognition. Human brains are awesome, but SAT solvers are not included in the factory model. His critique of deep learning is equally potent, and I was privileged to sit in one of his final in-person classes on these topics. Deep learning models perform tasks outside human cognition, such as recognizing impossible languages and, to a lesser extent, formal languages. Computer vision at the pixel level returns disparate results when one tweaks a few here and there, even though humans can’t tell a difference. Large-language-models are just another extension, and they likely couldn’t exist without illegally obtaining and using copyrighted materials, and performing surveillance on users. True, most tech companies have some form of this with search and social media, but this is a perverse leeching of people’s most intimate and private thoughts.

As it stands now, generative AI’s business model is bananas–electricity and water costs are rising quickly (externalities of no trouble to the leading contenders) as conglomerates squander billions of dollars on server farms, chips, and computation with advertising and dwell time as its major interests. The claim is, as made above, that destroying more of the natural world is inevitable, and only artificial general intelligence (AGI) can save us. It’s a catechism and mantra–repeat after me–AGI will save us all!

I believe this is untrue, as does Marcus. I go further, and perhaps this will tarnish me forever, but I have serious doubts that an alien machine intelligence will care one whit about us. Harari says as much in the latter section of his book. It doesn’t mean it would destroy us to save itself–I doubt even that is a given. If a chip in your pacemaker malfunctions, you and the pacemaker die. Viruses destroy hosts with almost no regard for themselves. Humans have destroyed much of the biosphere, and war seems more attractive to many than peace.

Many believe it’s too late for peace. Experts might secretly disparage the generative craze, but their overlords divert mountains of cash into the vanity project without real insight into the places it’ll take us. Are they crazy? I think not, but the danger is very real. I can’t speak to numbers on this, but I know, as I stated earlier, that some of us as ingenues longed for a machine intelligence which could right all wrongs and ensure peace. I was wrong about this; but I agreed earlier that deep learning was a craze, with the hope that scaling (more data, more machines, more power, more water) would create universally better models. There was an uptick, and the same occurred with LLMs. But the danger is supreme, and the willingness of the Trump 2.0 cabal to ban (an illegal ban, as it turns out) the fed and all fifty states from regulating AI for ten years almost ensures major mishaps and an economic crash (if not more than one.) There is more to say on the hyenas running the show, but it suffices simply to point out that even the base didn’t sign up for unaccountable AI (or regime change (see Venezuela) for that matter.

I believe peace is still possible, but I’ve increasingly come to the opinion that even AGI might be something we’re just not ready to tackle. It’s heartbreaking to consider that children in this world go to bed hungry. The gastroparesis plaguing me since 2017 led to a wholesale starvation condition, and it isn’t a bit pretty for an adult. I guess it’s time to tackle the next horseman.

Enshittification: Feast or Famine

I came across Cory Doctorow on DemocracyNow a month or so ago, and it was great fun just to listen to his almost manic command of tech as an industry and its complex history. He was stumping for his new book, which like this article, changed because the news cycle moved so quickly. It’s an incredibly accessible book for other technologists and pretty much anyone else.

In my own experience, most internet surfing has made its way to the phone, and because of mountains of ads (there is no end to the terrible ways they appear on the tiny phone screen), false restarts (page reloads not because of a problem but because the platform is stealing from the advertisers by showing ads more than once), clickbait and empty articles, and endless popups, I do much less of it now. Search engines tell lies as they push the organic search results further down the list. I’ve found a few such errors, such as a search engine incorrectly stating that Jimmy Carter had died (when it was his wife who had died). A fun fact about anti-nausea meds: they blur your vision. I cannot see print with my glasses on, and switching back and forth causes more nausea. So–I’m a medico-Luddite? Cory probably could come up with a better term–he utterly excels at it.

Streaming services are worse still–they’re slower, have ads, and cost more now than ever, even as their quality plummets. I used to understand the law of supply and demand–we viewers are the supply, so if there are fewer, they should, by demand, improve services and lower prices. They do just the opposite, and with each successful megamerge, the smaller studios are sucked into pump-and-dump crapfests. And they can ignore antitrust all they want–they just have to grease Trump’s tiny orange claws with unabashed bribery. Ugh.

The point is this: big box tech companies, streaming services, search engines, browsers, and social media are increasingly corrupted by the wrongheaded approach to business governance. I wrote a series of articles on Dean Baker’s Conservative Nanny State. Maximizing profits simply is not compatible with long term fiscal health. Some businesses are intrinsically less profitable than others, and balancing the books is not the same thing as exploiting every loophole imaginable to evergreen patents, deregulate Wall Street, and invest the people’s money in phony moneymaking ventures like cryp(is the new crap)tocurrency.

Stages of Shit

Doctorow begins by positing the business plan of the tech giants:

- Empower users, winning over many, including business customers

- Constrain and manipulate supply users to empower only business customers

- Constrain and manipulate business customers to claim the spoils

- Wallow in the pile of shit they’ve become

He outlines the path through case studies of Facebook, Google, Amazon, and others. It is, indeed, true that each of the largest tech companies at one time did respectable things in the halcyon yesteryear. The study of Google search is particularly interesting. The core search was developed by Google’s founders, and the company all but melted down as the vile maxim (wealth for self only) erased a product capable of enormous good. Social media presents many problems even in its genesis, but the business model above has made it impossible to even calculate the damage of misinformation, spoofing, and pretty much any gimmick one can consider. Microsoft built on Xerox to create a GUI that, for a time, was top of the line. Now, other tools are more competitive. Amazon once made it possible to connect readers and books–now they use countless dirty tricks to exploit authors and readers alike. There isn’t time to go through all of it here, but take my word that spending money on advertising through Kindle is a great pit of darkness. Jane Friedman documented it well.

Enshittocene? Show Me the Fleeceware!

The subsequent sections of his book cover the pathological causes of enshittification, as well as the study of the problem itself and possible remedies. Many causes exist, but much of it falls under the neoliberal order (anti-anti-trust) from Carter forward, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), relative comfort for tech workers, anti-union policies, regulatory capture, opposition to right-to-repair, and the disorganization of once in vogue tech workers in the face of automation. Examples are myriad, but one that stuck in my head is the baby monitors which begin at full capability, then internally switching off features to goad customers into paying a monthly fee. Another gem is the ink which powers HP’s printers–it’s $16K per gallon, and they pull every dirty trick under the sun to prevent third parties from providing it more cheaply. Turns out the cartridges contain a small chip capable of disabling the printer if it isn’t there and up-to-date. One might call it firmware, but I call it fleeceware.

Marcus and Harari offer analogous critiques, and, to my total expectation, the automation machine isn’t working as advertised. Tech workers are still incredibly valuable, but the gains made during COVID led to (my view here) the cruel realization that tech leadership would rather burn these commodities to scare the rest back into line. There are numerous grisly examples, such as Amazon using cameras to measure where the drivers’ eyes are at all times–they receive scores that impact performance assessments. Several drivers urinate in their trucks because of the absurd pace of what they do. They’re already treated like disposable machines, so is it hard to imagine that they won’t pursue even more malignant policy choices?

Curing the Mess

People often know when they’re ripped off. In America, grievance is king. Problem is this: often the hyenas yipping about it have one filthy claw in your pocket already. Doctorow believes that antitrust can remedy much of the disease. But forging a common narrative to sustain the cure could be very difficult. Biden was the most successful antitrust president since FDR, aiming not for his own legacy but for ours. I mentioned earlier issues one can find with the presidents; Biden was a president for the people. There was swift antitrust action taken against technofeudalists and their numerous subsidiaries. The European Union and others are carrying out lawsuits. Even Trump was carrying out some antitrust action, though greasing his palm with gold makes it go away. The thread of optimism here is this: any single success in the courtroom furnishes a blueprint for others, and lawyers are good at finding those things.

The mess leaves us vulnerable to extinction, but people are itching for change. Tech overlords prefer feast for themselves and famine for everyone else, but it could go the other way. But legal remedies aren’t sufficient to ensure a better future, even if they are necessary. Life and death rides on this.

The Conspiracy to End America: Life or Death

I first encountered Stuart Stevens when he spoke to DemocracyNow in 2020—It Was All a Lie was incredibly eye-opening, as I mentioned in a previous article. I can’t help but feel a bit of kinship, having also come from the south (if one can call Texas that.) His more recent book, The Conspiracy to End America, found its way to me late to the party. He is the horseman of death and life.

He argues that five irreducible primitives spell disaster for self-governing: if a movement can acquire these, it can metastasize, using the power of the state against itself. Cancer doesn’t care that it, too, dies when the host organism dies.

- Propagandists

- Support of a major party

- Financers

- Legal theories for cover

- Shock troops

We marked five years since the January 6 attack–it demonstrated that propagandists were alive and well, and shock troops were at-the-ready with travel paid by Trump’s machine. They received diplomatic cover when Trump sued every state he lost to overturn the election in 2020. They claimed that Trump was done. They claimed that someone else would have to defend the Constitution, or so said Mitch McConnell. Jack Smith demonstrated his case recently as Trump 2.0 seeks revenge against his perceived enemies. The GOP continued supporting Trump, and financers such as Musk and Thiel provided boundless support. Worse, SCOTUS has conferred legitimacy to Trump’s criminal enterprise. Project 2025 offers a roadmap for legal theories. None of these atoms were missing.

The Future

Stevens’ book appeared in print in 2023. He was deeply concerned that the regrouping of MAGA and its principal constituents would disparage Biden until no one could hear anything else. Biden received more votes than any American politician in history. Trump lost, and four years of his playing victim and fomenting insurrection should have been enough. But voters didn’t grasp this go-around that Trump possessed no plan, no argument, and no platform. Anger around affordability, hatred of immigrants, and a long tradition of white grievance heralded Trump’s return to office. It is astonishing–law and order party selects convicted felon over the former attorney general.

Stevens is easily the fourth horseman of the apocalypse–the narrative of our nation is waning, and though I don’t always agree with David Brooks, I think he’s right that a loss of community and society at large leads to the pits of human history. Hitler ascended because those who could stop him either were terrified, ecstatic, or in denial of his plans.

Conclusions

Each horseman represents both possibilities. Technology can underwrite war and peace, information networks can be used to conquest or liberation. Waning platform performance transfers the feast from the famished, but we could go either way. The deeper insight into an organization I long believed to ooze with corruption literally can destroy life or uphold it. It must be what we want–the future isn’t a given.

These authors are quite good, worthy of attention. It’s true, at the time of this writing, gobs of terrible things are happening. But each of the four says there are ways to pull ourselves out of the muck. In the meantime, find them each on Substack or through their websites: