Reader discretion advised.

It happened because of our disbelief, not despite it.

It’s been some time since I’ve contributed to this blog–a long crippling illness has kept me running low, and I genuinely believed 2024’s election would go differently. If you’re reading this, it’s most likely that you will agree with me in my profound concern about the ghoulish fascism mooring itself on the national soul. Eight years ago, I wrote my first blog post in the wake of Trump’s surprise victory in 2016. The charter of this blog has been to explain, imperfectly, the complex ecosystem of people, power, and history. More concrete, my purpose was varied: to explain to my contemporaries and peers in high tech why such an event could happen and to connect with the activist community eager and willing to invoke needed change. I feel I accomplished the first objective by reaching many. The second led to friendships to activists working for change, like George Polisner and Noam Chomsky. Chomsky read my work, and now that we’re in what essentially is a post-Chomsky world, I would happily put on my own headstone that Noam would reply to my posts within 90 minutes. Today is his 96th birthday, and a fitting day for my post to appear. Whether decent existence still awaits us after this remains to be seen. I’m tired, aging, and vulnerable.

Despite the ubiquitous works of others whose importance and prominence outstrips mine, we have found our way back to a horrifying outcome. My tendency would be to offer compassion to the weary in dark times. A refrain comes to mind after I spent a few days with my college history professor over the week of election: it is because, not despite. What do I mean? The virulent madness spreads because of its suicidal march to extinction, not despite. On the other hand, we refuse to give up, because it is perhaps hopeless, not despite.

My Own History

As I’ve written earlier, I was raised in north central Texas in a moderate-to-conservative family. My birth father (whom I’ve not seen in 28 years) proudly wore his confederate flag-emblazoned shirt around town, and my mother struggled to better herself through education. He was a drunk who abandoned his children; she pushed us to seek a better life through college.

We were evangelicals, though my parents’ divorce in 1987 earned our family certified letters that we could no longer attend our Assembly of God home church. We sought spiritual matters through a few other smaller churches before conceding perhaps our souls were already lost. I say it as a joke since I don’t believe most of it these days.

A quarter century ago, I sat in Pat Ledbetter’s American history class 1302 to study Reconstruction until the 1990s. It’s rare that I can point to any one class which guided my adult awareness of the world, the wokeness, if you will (or won’t since woke is now a racist epithet belonging to the class nigger.)

I learned about American exploits in Cuba, Central America, Africa, the Middle East, Malaysia, and East Timor. I learned that Reagan, Nixon, Eisenhower, McKinley, Kennedy, and Johnson ordered their surrogates to murder, pillage, and plunder in far away places. I wept at these facts; we were raised to believe Reagan had restored the Christian dignity of America, yet I learned of the thousands of people murdered in Grenada, Nicaragua, the Congo, and Indonesia.

How could a nation of the righteous do these things to the rest of the world? The implication was simple in my 19-year-old brain: if America committed atrocities, and the righteous would not, then America was not righteous. This crushed me–I felt helpless rather than empowered, despite the many men and women who struggled to achieve expansion of rights and to civilize a species rife with misery and mayhem. The typical 19-year-old wants the quick and sometimes dirty solution. Well, enough said about that.

I learned later that doing is more important than being; despair undermines the operation by dumping the manure of cynicism all over us. But movement doesn’t happen without motion; it’s a soundbite, but sometimes they comfort.

During the 2000 election cycle, I convinced myself that most everyone studied the same history imparted to me. I was a fool–millions of people voted against their interests for a failed businessman with the presidential name. I believed people would never vote to restore to power the chickenhawks like Cheney, Rumsfeld, and Wolfowitz after their hijinks in decades prior. Of course, if the votes had been counted, Al Gore would have been president. The Brooks Brothers riot astroturfed the malcontents during the recounts–these were not locals with genuine concern around voting tabulation. They were staffers from the RNC. It isn’t that different from the thousands of Trump signs blanketing Tucson and other swing state cities. No, it was because rather than despite.

September 11, 2001 reworked the system. I cried that day, but not just for the Americans lost. I knew our history–I knew we would destroy the lives and families of millions as our lumbering military bungled its way through the Middle East in search of apocryphal bogeymen. And that is exactly what happened: an ineffective, easily manipulated leader eagerly donned his cowboy hat and spurs as he claimed a fan favorite of politicians–a wartime president. Now, mind you, Congress did NOT declare war on Afghanistan and Iraq. But they signaled they would fund whatever Bush 2 wanted. Or rather, what Cheney wanted.

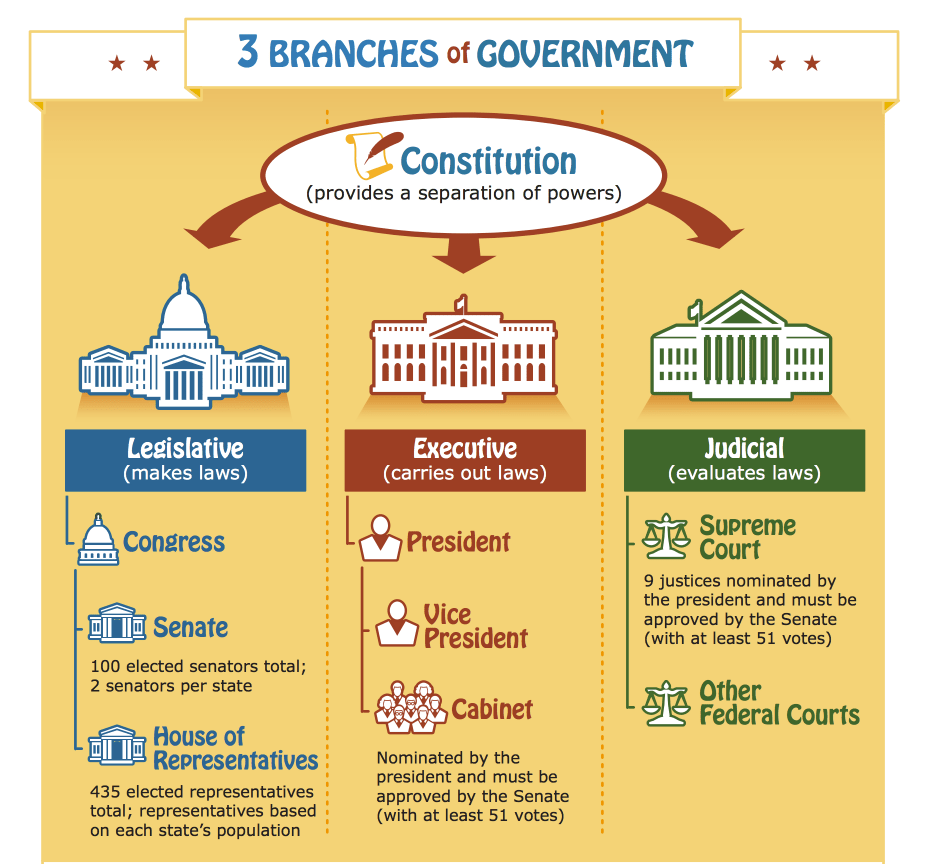

Reshaped Government Roles

The grisly truth is worse. The legislative branch is supposed to be the sole decider in whether we march into war. At least, that’s what the founding fathers intended. But something happened at the close of World War 2–the first and last deployment of nuclear weapons against a wartime foe. Fat Man and Little Boy rearranged military might in a way unforeseen by the founders. Though some debate the necessity of the bombings, I believe Japan was defeated. They floated the idea of surrender, but the Allied Powers refused, just as Bush 2 would refuse to treat with the Taliban when they offered to surrender Bin Laden. You might think America dropped the nukes despite their horrendous consequences, but, once more, think of because. Truman chomped at the bit, even when Hitler balked at wielding power some physicists believed would ignite the atmosphere. The late Daniel Ellsberg wrote a great book about the existential threat no one ever mentions during election season. The point here is that Congress abdicated its war-making power as subsequent presidents of both parties launched aggressive wars against third world nations.

Since that time, it seems that every president receives his opportunity to set the “legislative agenda.” I might be old-fashioned, but it seems that we should rename the branches of the federal government if the president decides what Congress passes. True, he can veto whatever he doesn’t like, but unlimited terms for the legislators means they would rather abdicate their authority than take the fall for the inevitable buyer’s remorse many voters feel each time we do this again. The president can serve two terms (though Trump has insisted otherwise.) He becomes a lame duck in term two, so America can reserve its ire for him when circumstances deteriorate.

There have been several campaigns to consolidate power within the executive, with Project 2025 being the most recent to receive prominence. Unitary executive theory was a predecessor, as were the works of People for the New American Century (PNAC). They range in scope, with all advocating for a fascist transformation of the federal government and society itself. The fact that 77 million people would vote for such an outcome screams disenchantment and fury.

The system is broken, but not because the institutions have failed people–people have failed the institutions. Mitch McConnell was booed by the Trump thugs at the RNC, despite paving the way for SCOTUS to overturn Roe v. Wade and grant sweeping, jaw-droppingly absurd immunity to all POTUSes, current and past. Worse yet, he could have prevented this mess by upholding his oath to protect the Constitution: the Senate should have convicted Trump after January 6. Instead, he bemoaned the lack of accountability, despite shaping SCOTUS and refusing to press his colleagues to ban Trump from office thenceforth. Why did they jeer him? Because he spoke against Trump, despite playing power games sufficient to coronate Trump for all time. But that’s just it–kissing the ring once isn’t enough. And his inner circle has sheltered numerous allies now in jail for the rampant corruption they shared with him.

Trump Was and Continues To Be No Biden

In 2016, cock-eyed optimists with wispy straggle beards could argue that Trump might make changes to improve the outlook for the labor class. I heard arguments about his outsider-ness, his stubbornness, and his success in business. I knew none of those would serve American interests since he was a Thanksgiving table of government handouts in his business dealings, that he couldn’t back away from even the most indefensible position, and that he somehow could straighten the whole of the federal government by knowing nothing about it. His people started a flag-craze, erecting thousands of TRUMP and MAGA flags. I don’t remember anyone putting a president’s name on a flag to fly alongside Stars and Stripes. Despite my doubts, I started the blog to share my perspective on the forlorn, forgotten working class. I could understand that part of their intentions, even if the xenophobia and misogyny took the lead. I attempted civility, steering away from the baser insults all of us might feel.

For those four years, I blogged regularly on Trump’s escapades and the stories of many who stood strong against him. I don’t want to rewrite what I wrote, so feel free to look at past posts yourself.

Decision 2024 is different. We’ve endured a Trump term, and the policy choices during COVID alone rise to the level of boneheaded, chaotic blunders, if not “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Over one million Americans died, and many others, myself included, suffer with long-term consequences of the first run. Even if grandma and grandpa are expendable (and I heard plenty say so), the job losses were catastrophic in 2020. Those of us who paid attention to those ugly four years cannot deny how much worse our world was. Everyday was filled with insanity–he was vicious, cruel, incompetent, and a disaster. Kamala’s words will come back to haunt us.

Biden assumed as president in January of 2021, and he made enormous headway in both undoing the damage of Trump’s term and advocating hard for student borrowers, victims of gun violence, infrastructure improvements, and much more. Politico‘s article explains it well. His accomplishments include strengthening the CDC and hardening our response to future pandemics, passing infrastructure bills, working to reduce financial burdens on student borrowers, and presiding over an economic recovery. What did he do wrong?

For four years, Trump’s surrogates (such as hyenas like Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy) and MAGA clowns in Congress have schemed and plotted, obstructing Biden and congressional Democrats. These rightwing ideologues spent countless dollars demonizing transgendered Americans and immigrants, persuading people even in Tucson 60 miles north of the border that we are awash in immigrant crime. Newsflash for anyone who cares–there is no migrant crime problem that’s any worse than it was when Trump was president. It’s stunning, but I assume social media remains a lifeline for people looking for things to hate and fear. The RNC spent $250M on attacking the trans community, and Democratic pundits and politicians claim this led to Kamala’s defeat, despite her saying almost nothing on it. The heartless ads produced show pictures of huge men in wigs towering over women basketball players and ballerinas. Why support such cruelty? It was because, not despite.

Their attack ads originally focused on Biden’s age, despite Trump’s very clear cognitive decline. Or rather, because: Trump is easily manipulated with flattery, providing an opening to the greedy among his inner circle. One of his attorneys is already cashing in, selling administration posts to the highest bidder. Trump’s Caligula cabinet picks are so ridiculous, I won’t delve into the details here. It suffices to saw that national security and smooth access to government agencies will be longer term casualties in Musk’s war on America. Even the mainstream media paid excessive attention to Biden’s gaffes while ignoring Trump’s lunacy. After the attempted assassination of Trump, his supporters claimed that Democratic rhetoric was to blame. Nevermind Trump’s own violent diction, fantasizing in public about shooting Liz Cheney, executing immigrants, and jailing all his opponents. Nevermind that it was a Republican who tried to kill him. Nevermind… Ah, whatever.

The point I would make here is that Trump is NOT an unknown quantity this time. We know what his years were like, and several million people stayed home on election day rather than help choose the first woman president. She, like Biden before her, would play with everyone, not just her friends. She didn’t lose because she ran her campaign badly–she articulated her plan well, she was civil, and she was the sole major candidate to treat with the Republican’s central issue: immigration. She was a prosecutor–law and order conservatives should have cheered this. Instead, they chose a convicted felon who stole and imperiled national secrets, who attempted to overthrow the government with violence, and who attempted to change the outcome of an election he didn’t like.

Trump supporters had ample evidence of the harm he could unleash. They chose him in any case, and it means America failed that class and we have to take it once more. I never believed Trump would shock and awe his critics into joining his cause. Does that mean I am among the “enemy within” Trump promises to eliminate with the military?

New (or maybe old?) tactics include:

- Threatening to wield martial law in the extirpation of illegals

- Aiming to create high tariffs (critiqued by Biden) against countries with manufacturing bases far outpacing what’s left of America’s semi-skilled infrastructure

- Spreading lies about immigrants such as accusing Haitian refugees in the heartland feasting on dogs and cats (Vance conceded the lie by suggesting that the media yearns for false flags to talk about issues true to the American people… Confused? Yeah, me too)

- Demonizing trans children, school teachers, and Democrats to prove their progressive causes are more important than the economic ones Harris and Biden both articulated quite well

I could list more, but I think it’s better to leave my past posts as a testament to his many failings; they are numerous like the stars in the heavens and fleas on a dog. It’s important to take a step back to consider his campaign “promises.” Tariffs and ending illegals’ stay in America will wreck the financial market and cripple the consumer base. The point I would make here is that his plans aren’t really plans at all, and his supporters who scream about it don’t understand the first thing about them.

Localizing the Effort

Rather than learning about how things work, Americans stew and seethe in crippling anger. Pew and other polling organizations have reported this for some years now. What is new to me is the degree of hoodlumry even in the very nice neighborhood I call home in Tucson. Signs blanket-astroturfed Tucson drawing inane comparisons: Trump=Low Prices, Kamala=High Prices, and the like. I thought voters were smarter. My physical limitations notwithstanding, I placed $200 worth of Harris/Walz signs on the two thoroughfares near my home, and they were stolen and defaced within 24 hours of their placement. Keep in mind this is a 60 Blue/40 Red spot in Tucson, yet a thousand or more Trump signs went up. Some of those were stolen, but ALL of my signs were destroyed. These aren’t brown hoards rushing us from the border–they’re middle-aged and older white men (like myself) who think nothing of tearing up another’s property and right to speech. Kelly and I replaced the signs on two occasions, and we were met with harassment and derision by some of the passers-by. Though I voted by mail, an elderly friend of mine needed to vote in-person, so I drove him there. In the fifteen minutes I sat in the waiting area, conspicuously MAGA folk appeared to harass the poll worker and pull others around them into the grand show of it they were putting on. Again, these are white men. Grown narcissistic men with nothing better to do.

In the five years since moving to Tucson, I’ve experienced only a few instances of crime committed against me. It was almost always a white man (once an old white woman), NEVER a brown illegal or trans person or bloodsucking schoolteacher with designs on your kids or whatever else gives these people nightmares. This is anecdotal, but it’s very much worth pointing out.

Tilting at Them Thar Windmills

I visited my hometown Gainesville in Texas around the election to be with a dear friend in the hospital. In the years since I moved away, a few windmills have sprouted northeast of town. And what attempt at green energy would be without the hysterical signage of fools afraid of it? But I was immediately struck at the utter lack of political signs anywhere in town. Of course, it’s a safely red district, so the Musk/Ramaswamy/Koch money machine didn’t direct their deepfake signs there. But there were a few choice markers, like one deriding Tim Walz as a klutz. My brother Robin often bemoans that there are few things “to put one’s back up against” anymore–it used to be that Republicans would delight in a candidate retired from the military over a draft-dodger like Trump, but it is no more. They swing at everything, including the constituencies they once praised. In my hometown, they posted a billboard of Walz with the word “KNUCKLEHEAD” painted beneath him. To be clear, Walz has much more in common with my old Gainesville than Trump or even Vance. But is this a surprise? Trump ridiculed John McCain, a man who once meant something to Republicans. It’s now just power lust, feral, aimed at everything, and bent on domination.

The numbers are interesting: Harris received roughly 74.5M votes to Trump’s 77.0M. In 2020, Biden received 81.3M to Trump’s 74.2M. When adjusted for the growth of the electorate, neither party scored as well as they did in 2020. Trump came closer with an increase of 3.7% voter share, but this still lagged the 5% true growth from 2020 to 2024. What does it mean? The 2024 election simply attracted many million fewer voters than did the event four years ago. A narrative frequently pushed by progressives is that if everyone voted, we would win. At the least, this year’s election affirms this. 66.6% of the electorate voted in 2020, versus 63.7% in 2024. The raw difference in the electorate was 12 million, but the difference in voting blocks was 4 million, down from the 8 million required to meet 2020’s same percentage. True, these are the sorts of facts we progressives claw and pick over to find that one thing we can safely place our backs against. If anything, it underscores the lack of a mandate for the Republicans (and they have failed to earn a majority of votes cast since 2004.) But the ‘winner-takes-all’ feature of our system assigns power to the winning side with little power resting with the losing party. In other words, Trump, as has been true in all elections with him at the top of the ticket, will rule as if he received a majority of the popular vote. Both Biden and Obama, by contrast, won with majority popular votes.

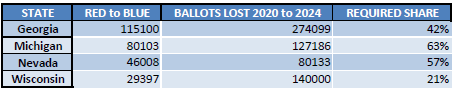

It’s worth taking a moment to look at deltas one cannot obtain without painstaking data entry. First, I computed the number of votes lost from 2020 to 2024 for each state and party. Second, I determined the number of votes needed to flip a state from red to blue. Finally, I calculated the share of lost votes needed to accomplish that change. The states where this was even possible appear below–the hill was a little steep but quite possible. The conventional wisdom that Democrats win if more people vote does seem to be correct.

It doesn’t affect the pragmatics one wit–Trump will govern as if a supermajority of Americans wanted him. He barely did better than his previous outings, succeeding because millions didn’t vote. The challenge for minority rule is treating with the disenfranchised. More people voted for Hillary in 2016 than Trump, but our voices were more than just stifled: he delayed aid to California during wildfires (and he promises to do worse the second time around.) The real problem is that Trump is crazy, and if others tell him that he won, like the perpetual victim Kari Lake, he finds himself needing to believe it. It’s part of the myth-con.

But with the good medicine comes the bad: Trump’s hold on sanity is gone, along with any hope that the two coequal branches can place him in check. The billionaires backing him are in agreement with Harris: Trump is weak and easily manipulated. He’s already picked a grab-bag of cabinet toadies claiming they’ll do his bidding, though the real litmus test requires them to shower him with praise. His choices are inept and reckless: they don’t know the first thing about leading an organization of any kind, let alone a federal agency. The ensuing chaos will suit Trump to a tee.

Speaking of billionaires, it’s worth mentioning that Elon Musk’s embrace of all things Trump following the assassination attempt last summer didn’t mark the off-the-deep-end moment for the world’s richest person. In the past few years, he’s made increasingly crazy statements, fueling his promotions with his wealth and a folk-hero status to the technocrats. He is a splendid example of the danger of believing one’s own press: he’s the richest person, so he must know what he’s saying. No, he is insane because of his wealth, not despite it.

Narcissist Musk tilts at them thar windmills: destroying Twitter in the name of free speech, enforcing illegal and hazardous constraints on Tesla workers to make the otherwise unprofitable business viable, and fighting literally dozens of suits brought by states and the federal government for workplace violations while executing and bankrolling dozens more suits against his enemies. His true skill is playing the Machiavellian, arguing for his own First Amendment while blasting others for speaking up. He and DEI-foe Ramaswamy plan to destroy the civil service, replacing it with workaholics who faint after 12-hour shifts. Good luck finding that.

Musk’s insanity makes him a true enemy within, an immigrant playing cuckoo bird as an innovator and savior to humanity. He has, like Rupert Murdoch before him, invaded our country on a quest to hollow us out from the inside. Vance is another cuckoo, claiming an Appalachian homespun origin while attending ivy league schools. Like George Santos, he has learned the Roy Cohn art of saying whatever is necessary to win.

This is a pattern: Trump’s inner orbit attracts the same sort of myth-conning that has propelled him to the presidency now twice. RFK, Jr. fits the bill–he’s unscientific, narcissistic, and just plain nuts. He believes vaccines cause autism, that wireless tech causes cancer, and that COVID is a conspiracy against whites and blacks designed by the Chinese. Jesus, I don’t know what else to say. He will lead the FDA.

What more? A wrestling exec will lead the Department of Education, a news host the Defense Department, an NFL alum the Department of Urban Planning, another news host the Department of Transportation. Ugh, never mind. Bob Woodward squinted as hard as he could to find the micron of optimism, but he’s since changed his mind.

Woke and DEI to Blame?

And we mustn’t stop there: Harris’s defeat led pundits to proclaim the death of wokeness, blackness, diversity, and inclusiveness. Maybe Harris’s blackness and woman-ness kept people home, but I don’t think so. It takes genius not to see it, to quote Chomsky. One would never say that a cancer survivor losing an election means that we can’t treat cancer anymore–such a fool would be laughed right off the soundstage.

Blaming wokeness for Kamala’s loss is no less idiotic than blaming oncology because a cancer survivor loses an election.

It comes down to the narrative that Trump’s supporters pushed from the beginning–he’s better with the economy. People are tired of paying more for less, despite the requisite cycle to recovery from recessions. Allan Lichtman and his keys predicted Harris to win based on indicators that should have been in her favor. I believe the true culprit is in the “doppelganger” world I described a few years ago. Naomi Klein wrote a book of the same name last year. Information is asymmetric, preselected by unaccountable algorithms running in social media platforms. People genuinely believe that the immigrant crimewave is real. They believe trans people are perverted men wanting to push their way into women’s sports and bathrooms. They believe DEI initiatives undermine the fabric of business and family. They believe immigrants are roasting America’s dogs and cats. How does this happen? Why do people believe these things without actually seeing them happen?

I think it comes down to a very human need to manage anger and despair. People know eggs cost twice as much as they did four years ago. They’re angry that the rich continue to get richer while everyone else pays more for less. Trump’s backers know this all-too-well, and refocusing extant anger is propaganda 101.

DEI is an enemy for Ramaswamy and Musk: in the latter’s view, it is discriminatory. Of course, these are not data-informed positions–they’ve fallen for a gimmick as old as civilization itself: conflating rare, good fortune with wisdom. Money is the thing that matters to Trump in any case.

Musk has given us plenty of samples of his inner workings, threatening federal workers and anyone he perceives as the enemy. It turns out that he’s also quite stupid, targeting employees who work on ecological diversification rather than diversity and inclusion. No matter the brain rot gnawing at him, his tactics mobilize Trump’s brownshirts to drive these people from their homes. The DOGE (department of government efficiency) promises to purge the civil service of practically all expertise, with half-wit loyalists prepared to take up residence. It is a grim portent of what Trump’s second term promises: cruelty and vengeance.

How Goes the Myth-Con?

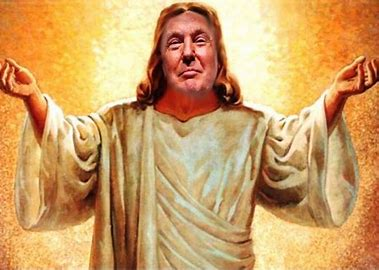

Rallying otherwise decent people to do evil isn’t new. As we’ve observed before, totalitarianism begins not with a twirling mustachio and his manifesto to do harm, but rather a white knight claiming to want to save those decent people. The most tyrannical regimes in the world invoke their authority from democracy, divinity, and freedom. They don’t appear in the shadows, twirling their mustaches. Except when they do: Trump isn’t popular, nor has he ever been. But he is a hero to his ardent supporters. While visiting Phoenix, I came across a lot with twenty or so American flags, together with a poster of Trump which canonizes him by the two impeachments and one assassination attempt. (This replaced a “Let’s Go Brandon” flag this brain trust flew over his house.) In other words, the bad guys wanted Trump gone, so that means he’s a good guy. I call this the myth-con. He is deified precisely because of consequences deriving from the response he’s coerced from others.

Like Hitler before him, Trump’s attempted assassination was carried out by a rightwing gunman who snapped. His surrogates were quick to blame the Democrats and their rhetoric for the attack, despite his very, very long history of ratcheting up violent threats. He even went so far as to threaten Liz Cheney’s life by firing squad. She voted with his bloc over 95% of the time, but resisting the rise of fascism is just a bridge to far.

To be clear, the conservative chicken hawks of yesterday are to blame for Trump, even if they decided he was bad news later on. Karl Rove, Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz, Dick Cheney, George HW Bush, and many others sought to radicalize the federal government through their Congressional allies and, of course, the figure-heads George W. Bush and Ronald Reagan. Former Republican strategist Stuart Stevens says this was always the core of his party’s intent. I remember the Bush administration destroying careers of CIA Agent Valerie Plame and her husband Joseph Wilson because the latter opposed the war in Iraq in his capacity as US diplomat. The release of her identity imperiled her contacts, but we already know that the fascist calculus demands total obedience. Though Scooter Libby took the fall, it’s possible the conspiracy rose all the way to the vice president’s office.

I don’t remember believing it was as consequential as the millions displaced and murdered by Bush’s illegal wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, but it demonstrates a hatred even for the sacred cows who oppose the feral party. Trump (the draft-dodging crook) belittled John McCain (the veteran and tortured POW), despite the military sitting atop the conservative pantheon of what is good and right. McCain died, and his Arizona voted Trump back to power in 2024. The myth-con requires key ingredients: the gladiator struggles against a corrupt system with nothing less than divine calling to save the marginalized and disaffected from aggressive hoards. Hitler had his Jews, Trump has his Mexicans.

Let’s take these ingredients: Trump is a gladiator. He swings at everything because, not despite his moral and personal failings. The system is corrupt: Americans know that the economic order is unfair. Many work hard, few receive rewards. For years, they’ve paid more for eggs and gasoline–though these aren’t the only metrics of value, they’re enough to enrage ordinary people. The white working and uneducated classes are deeply disaffected–DEI and wokeness appears to benefit brown women, and that bothers them. Jordan Peterson and Joe Rogan tell young white men that they’re victims, too. Because they’re already unhappy, it’s easy to blame the deepfake hoards pouring across the border. Immigrant crime is almost nonexistent, but social media locks people online by triggering the most powerful emotions. They decide that the Haitians eat American pets because they’re angry about longer working hours with less pay, and the regressive sales tax that is inflation. The “otherness” easily depicts the Democratic choice–she’s a black woman. Never mind that she ran one of the most conservative Democratic campaigns of the past fifty years. The myth-con can succeed on the strength of well-intentioned pollsters and pundits who play to the state narrative, as you can see in Bill Maher’s recent interview with Jane Fonda. Rather than admit that Trumpism is avarice and bigotry, his surrogates would insist that Kamala is for “they/them”. Biden was more openly pro-LGBTQ, but he’s an old white dude with a good Christian name.

The myth-con can succeed on the strength of well-intentioned pollsters and pundits who play to the base narrative.

The last ingredient is actually the hardest for me to understand: the divine calling. Trump himself claimed that God saved him from assassination so he could save the country. I would argue that people believe lionize Trump despite his cruelty and utter absence of morality. But I believe, like my history professor before me, that it is because of these things. Fanatical apologists believe he will repair their faith in decline. Others call him King David, Jehu, or Moses: his failings are the reason for his deification. Trump’s appointments to SCOTUS overturned Roe v. Wade, a long-sought event celebrated in most quarters of conservative Christendom. It doesn’t matter what Trump says or does. Abusing women, paying porn stars, and elevating to powerful positions the most corrupt among us augments rather than diminishes him in their judgment.

It’s unfocused, raw anger. And they’re easily manipulated, like Trump himself. All the ingredients are there, despite much of the mess following Trump’s botched COVID response. But there’s no taste for thinking things through, as disappointing as it is. Even mainstream media fails spectacularly in hitting the salient points hard enough. They announce dispassionately that Trump will seek revenge against his many real and imagined enemies, as though this is normal. Ignorance seems necessary for a demagogue to ascend. Ladies, gentlemen, and everyone else: we’ve been myth-conned.

The how of the myth-con is pretty clear. But why do this? Is being the richest man in the world insufficient for Elon Musk? Can Trump not just enjoy his last years with adoring mobs and merchandise? No, and no: no amount of money will ever satisfy Musk, and nothing short of the throne is good enough for Trump. It is because, not despite. Trump learned long ago from Roy Cohn that leaning into the accusations is the way to beat them. Bob Woodward said in 2020 that he didn’t believe Trump knew the difference between fact and fiction. I would tend to agree–Trump just emits shit, and his lapdogs scarf it down. They twist and twirl to keep it pieced together, but the whole of it will fall.

But Why? For God’s Sake, Why?

When my grandmother and her older sister were growing up in Oklahoma in the 1920s and 1930s, they fought from time to time, as children often do. But there was a sharp difference between their respective tenors: when her sister was angry, she broke my grandmother’s toys; when she was angry, she refrained from it. Her rationale was, “I knew we wouldn’t be mad later.” That is, for anyone who cares to know, perhaps the biggest difference between the two political parties in America. The Democrats play to the mainstream to get work done, while the Republicans obstruct and destroy when not in power, then grasp and claw once they persuade the electorate that the Democrats are responsible. Don’t believe me? Mitch McConnell wasn’t the first obstructionist; one can go back to the 1990s for the shitshow that was Gingrich’s Contract with America. Clinton was as close to a classical Republican as we’ve had in that office since the Reagan years, and they still spent years investigating and slandering him. Many of those same hyenas are still in Congress, and they think Trump’s actions are just fine.

Soon, we won’t need the Republicans to break all our toys–catastrophic climate change and nuclear proliferation remain the two greatest threats to our biosphere with no coherent mainstream message.

But it isn’t satisfying enough to say that they’re rotten apples–we progressives often strain to find the silver lining, that one explanation or motivation that can save their souls. But I’ll say it here–my grandmother’s sister was just plain bad. Sure, she was mentally ill (probably schizophrenia), but she was monstrously abusive to her daughter. Long after her sister’s death, my grandmother felt for her. She was charitable in that regard, even when it was repaid with viciousness.

Soon, we won’t need the Republicans to break all our toys–catastrophic climate change and nuclear proliferation remain the two greatest threats to our biosphere with no coherent mainstream message. The former dwells only in the minds of thinking people, utterly disregarded by Trump and his flunkies. But I believe the Rupert Murdochs and the Elon Musks have surrendered hope that this world can be saved. But I’ll repeat it: if the world cannot be saved, it is because rather than despite their unbelief. The money Musk dumped into Trump’s war chest could have been spent solving rather than creating problems. The billion dollars spent on the election itself could have fixed a plethora of issues throughout the world. Instead, that money finds its ways into deeper pockets.

Taking Our Lumps

As I said earlier, I’ve tried to explain the outcomes precisely because I am a progressive–I want to believe that there is redemption for the wicked. But the 77 million people who chose Trump, along with the 50 million who refused to vote, know now what they’re getting. For another term, we will contend with lawless chaos with an even sharper edge. The evangelicals who selected a sex offender can kneel at all the crosses they want. The attack dog brownshirts answering Trump’s call to chase good people out of their own homes can gush at the flag and praise law and order as they step on Capitol policemen’s faces. SCOTUS has assured Trump everlasting immunity, and therefore he has nothing to fear. I wish I could say the same for us.

Is there a next move? Biden is thinking of pardoning Trump’s intended victims–that isn’t the reason the president has this power, but it exists to permit him the opportunity to cure legal failures. The usual folk will oppose Trump’s batshit crazy agenda. Musk will help him weaponize the soon-to-be-gutted bureaucracy to isolate and eradicate enemies. The House once more voted to supply the president with unilateral power in classifying nonprofits as terrorist. With AI tools, they plan to eliminate the “enemy from within,” or the ordinary folk French revolutionaries claimed to represent, even as they killed them during the Reign of Terror. Obviously, opposing the use of unaccountable technology will become a staple. The one silver lining I can find in all this is that Trump’s lone contribution to any enterprise is the sowing of discord and chaos. It might be difficult for him to execute an agenda while riding the highs and lows of dementia and insanity. But I’m running low on hope. I’m aging, ailing, and grieving.

Are there steps forward? Yes!

- Read about American history. Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States features many ways forward, none of which are secret. Labor unions, solidarity, and mutual support make it possible to build strength.

- Listen to sensible sources of information. Timothy Snyder, Robert Reich, and Amy Goodman supply that, along with inspiration and wisdom. The day is dark, and though cruelty seems to have won a major victory, people can surprise us. But it isn’t enough to just sit and wait for the world we want–it requires dedication and very hard work.

- Kick nihilism to the curb. I was once told by a brother that kindness to a person with terminal cancer was a waste, because, “He was gonna fucking die anyway.” I disagree–that’s when we have the opportunity to show the universe who and what we are. Candles burn brightest in the darkest spaces.

- Education is a categorical imperative. Learn all you can. The generative networks used to cheat on homework and manipulate users will drain brains everywhere. You’ll be rare as hens’ teeth if you know anything about anything.

- Support independent media. Join sites like civ.works and Democracy Now.

- Boycott the bad actors.

- Talk to each other. People will surprise you if you give them a chance.

- Protect each other. Stand in solidarity with trans, immigrants, women, blacks, gay people, elderly people, and, well, people.

- Strengthen education. Generative AI has hurtled us closer to educational bankruptcy. It is unaccountable and dangerous, designed principally to retain platform users until they convert (buy something.)

- Do NOT fall for the myth-con, no matter who promotes it. Take sociopaths at their word.

- Love each other.

This will be my final post for a season. I’ve spent considerable time researching and writing, and though the work is far from finished, I’m exhausted. I will still be here, so don’t feel as though you can’t reach out. I hope for better health, a return to my career, and a better world. Because, not despite.